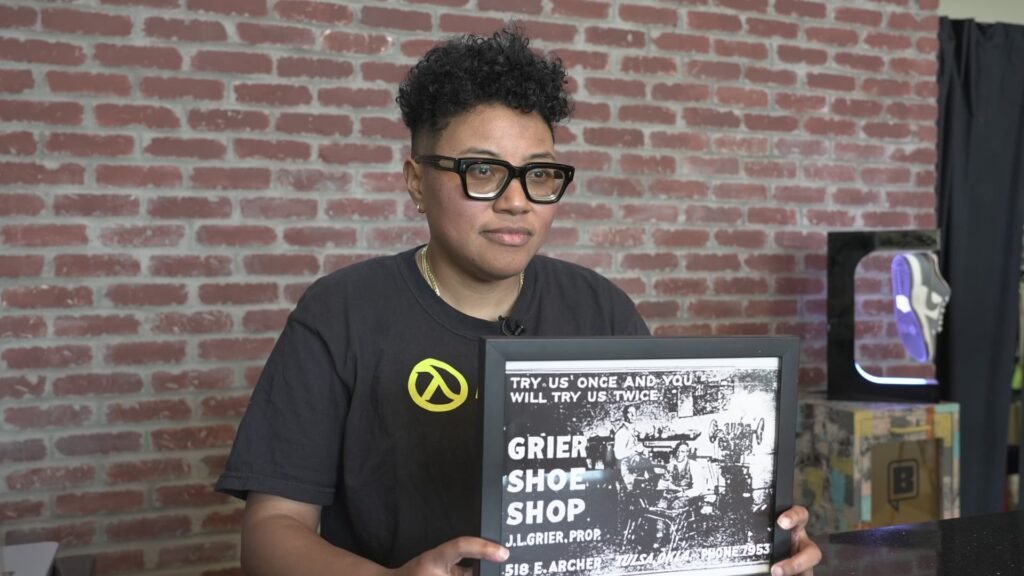

Venita Cooper, founder of Silhouette Sneakers & Art in the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Parnia Mazar | NBC News.

TULSA — Surrounded by rows of colorful shoes lining the walls of Silhouette Sneakers & Art, framed black-and-white photos remind owner Venita Cooper of the giants on whose shoulders she stands.

The photo shows the company name Grier Shoe Shop and its address superimposed. The address is part of the area known as Black Wall Street. The business occupied the Cooper building until it was destroyed during the Tulsa Race Massacre more than a century ago.

Local supporters say the area has seen several waves of black entrepreneurship in the decades since Greer to Silhouette. They are especially enthusiastic about the Renaissance era of innovation and technology, after desegregation in 2020 increased corporate and societal interest in uplifting Black Americans.

“We’re trying to revitalize this place, build a successful business here, and take back what was taken from us,” Cooper said in an interview.

Cooper also runs an artificial intelligence platform for the shoe resale market called Arbit. With these ventures, she joins a growing class of Black entrepreneurs who tap into Tulsa’s history for inspiration and support resources.

She attended Act House, an accelerator program for entrepreneurs of color. The program offers her $70,000 investment with no interest or capital requirements, and non-local participants relocate to Oklahoma’s second largest city to work with her colleagues and other professionals.

difficult history

Act House founder Dominic Ardis said bringing participants to Tulsa for a few months will help them understand how they fit into the bigger picture of minority entrepreneurship. Ta. Some companies that have not yet joined the community remain beyond the accelerator’s conclusion, adding their burgeoning businesses to the region’s growing ecosystem of minority-owned companies.

Act House is part of an organization dedicated to supporting Tulsa’s Black-owned businesses, a mission these officials believe is especially important given Tulsa’s checkered history. ing.

Dominic Ardis, founder of Act House Accelerator in Tulsa, Oklahoma;

Parnia Mazar | NBC News.

The Greenwood neighborhood, more formally known as Black Wall Street, was attacked by a white mob on May 31, 1921. The incident would later be recognized as one of the worst racial massacres in American history. More than 1,000 businesses and homes were attacked and up to 300 black people were killed as mobs torched neighborhoods.

That history received new attention after the killing of George Floyd in 2020 and during the 100th anniversary of the massacre in 2021. In the Tulsa suburbs, supporters say some of the interest from businesses supporting Black businesses has waned with subsequent increases in interest rates and economic uncertainty. .

But within local communities, groups continue to try to rebuild what was lost by empowering the next generation of entrepreneurs. One way to unify disparate efforts among stakeholders to best serve founders is through Build In Tulsa, a network of accelerators, investors, and other companies.

Ashli Sims, managing director of Build in Tulsa, said Tulsa is increasingly recognized as a hotspot for emerging technology, and given its history, why it’s important for Black entrepreneurs to go there. He said he understood it more clearly. Sims, who grew up in the city, said efforts are being made to counter the once-pervasive idea of Black Wall Street that people should leave it to find success.

“I want young black kids growing up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to look around and see the tech startups, see the CEOs, the founders, the innovators,” Sims said. “I want them to see wealth and know that it’s part of their future.”

Sims said for entrepreneurs this means showing they don’t have to move to a coastal city to take their venture to the next level.

Shoes on display on the wall at Silhouette Sneakers & Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Parnia Mazar | NBC News.

Build in Tulsa recently opened a space where entrepreneurs of color can collaborate and attend meetings. This his three-story building is located at the corner of North Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Conciliation Way, the latter of which was previously occupied by Ku She Klux figures with suspected ties to the She Klan. It was renamed in 2019 out of respect.

Tulsa’s physical community was paramount to founders like Edna Martinson, who founded Boddle, a company that offers 3D games to encourage learning for children. Through Tulsa, Act House alumni now feel part of the national black entrepreneurship community and are gaining recognition at more popular events for owners, such as Art Basel in Miami and South by Southwest in Austin. I was able to connect.

“It’s not just like Tulsa,” Martinson said. “This really is like a gateway into the broader national community of founders and ecosystem builders of color.”

Funding challenges

Despite progress, advocates and entrepreneurs are quickly realizing that the patchwork of organizations providing support is not eliminating the inequities faced by Black founders across the country. The biggest obstacle that many people point to is the difficulty of raising funds.

Disparities exist at every level. A 2016 Stanford University study found that black entrepreneurs start with about $500 in outside capital, compared to white entrepreneurs with $18,500. While the amounts are modest for both groups, the National Bureau of Economic Research reports that white-owned startups receive five times more money from family members and other insiders than black-owned startups. It is said that they are doing so.

According to Crunchbase, black founders received just 0.48% of the amount of venture capital in 2023. Traditional financing methods are also hampered by practices such as personal collateral requirements, making it difficult for people without generational wealth.

“It’s literally exhausting,” said LaTanya White, founder of Concept Creative Group, a company focused on business development and wealth transfer among Black founders. “All the while, you’re still trying to build a business and create something that will open doors for your family and community for generations to come.”

These challenges further exacerbate an already dire picture of the equality situation within business. Less than 3% of U.S. businesses are black-owned, even though the racial group makes up more than 12% of the country’s population, according to the latest federal data analyzed by CNBC.

Olaoluwa Adesanya is one of the entrepreneurs struggling to raise funds. Adesanya has noticed that venture capitalists are hesitant to invest in hardware-focused technology companies, but he has been able to get funding from a diverse group of founders of color. did it.

In addition to his participation in Act House, he has received tens of thousands of dollars from programs such as Afrotech and Harvard Business School’s Pitch Contest for Black Founders. He also secured grants from Black Wall Street organizations.

Adesanya said both financial support and community support in Tulsa have been critical to improving his product, palm plugs, for improving hand movement. Before stepping on the gas, Adesanya had a prototype, but was always worried it would break. Now, he frequently collects compliments on its design and quality.

“It’s still very difficult,” said Adesanya, who has returned to Seattle but is considering a permanent move to Tulsa. “But I’m also very appreciative of the Black community and I’m also very grateful that they’ve gotten us to where we are today.”

There’s also evidence that Black founders have a harder time securing government grants and contracts, says the Center for Black Entrepreneurship, a partnership of two Historically Black Colleges and Universities and the Black Economic Alliance Foundation. Director Grant Warner said. He said one of the clearest examples he had seen was identical applications for government awards that were approved only after a white person’s name was changed before a black person’s name.

“The dream of our predecessors”

Entrepreneurship can seem especially risky for Black people trying to preserve their families’ economic standing, said James Lowery, author of two books on minority wealth. Part of the reason, he says, is because they don’t want to sacrifice the security that previous generations had when breaking into American businesses.

Black people don’t always have the luxury of seeing other racial groups look at the models of successful people who have started their own companies within their own communities, he said. Still, Lowery said he’s excited to see more Black students attend business school and consider creating large-scale ventures.

“If you’re a laggard and you’re competing with people who have been entrepreneurs for generations, even within your family, you’re not going to be able to compete with people who have been entrepreneurs for generations, even within your family,” said Rowley, who is also a senior advisor on workforce and supply chain diversity at Boston Consulting Group. It’s a thing,” he says. “We’re playing catch-up, but we’re making progress.”

The Black Wall Street mural in the Greenwood neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on Friday, June 19, 2020. Greenwood, known as Black Wall Street, was one of the most prosperous African American enclaves in the United States until it was destroyed by riots. The white mob of 1921.

Christopher Kreese Bloomberg via Getty Images

Nationally, advocates see government programs that could help level the playing field for founders of color. For example, the Uplift Act would provide resources to create business incubators on college campuses and community colleges that historically serve black and minority populations. He received more than 1,000 applications for fewer than 50 spots in the Minority Business Development Agency’s Capital Reserve Program, which helps disadvantaged entrepreneurs expand their businesses.

Black entrepreneurs and stakeholders point to resilience as a key quality that helps founders succeed despite these unique obstacles. In fact, academic models show that female and minority founders exhibit higher levels of resilience due to a combination of challenges and support structures.

Adesanya and others who come to Tulsa can see and feel the resilience of those who came before them in the face of hardship.

From sidewalk signs marking pre-genocide businesses to museums dedicated to the history of Black Wall Street, reminders of the past help founders understand their place in a long legacy. It helps me better understand what’s going on. And they say it gives them the inspiration to break down barriers for themselves and those who come next.

“We are truly the dream of our ancestors,” Adesanya said. “What we are doing is what they dreamed of and what they suffered for.”

— NBC’s Shaquille Brewster, Parnia Mazhar and Andrew Davis contributed to this report.

Read the rest of this story harry jackson now 5pm ET.